This work contextualizes the experiences of today’s environmental violence in Colfax within local legacies of white supremacist violence. The Colfax Massacre of 1873 was one of the deadliest terror events in U.S. history: Black militiamen occupied the Colfax courthouse in an attempt to preserve their votes cast in a presidential election (an election characterized by white southerners organizing against Reconstruction policies). Between 50-153 Black Americans were killed by a white supremacist mob comprised of former Confederate soldiers and Ku Klux Klan members. Some time after the massacre, prominent perpetrators were arrested and their fate was decided in United States v. Cruikshank (1876): the decision effectively ended Reconstruction by neutering the president’s ability to use military force to protect African-Americans, previously granted through the Enforcement Acts of 1870.

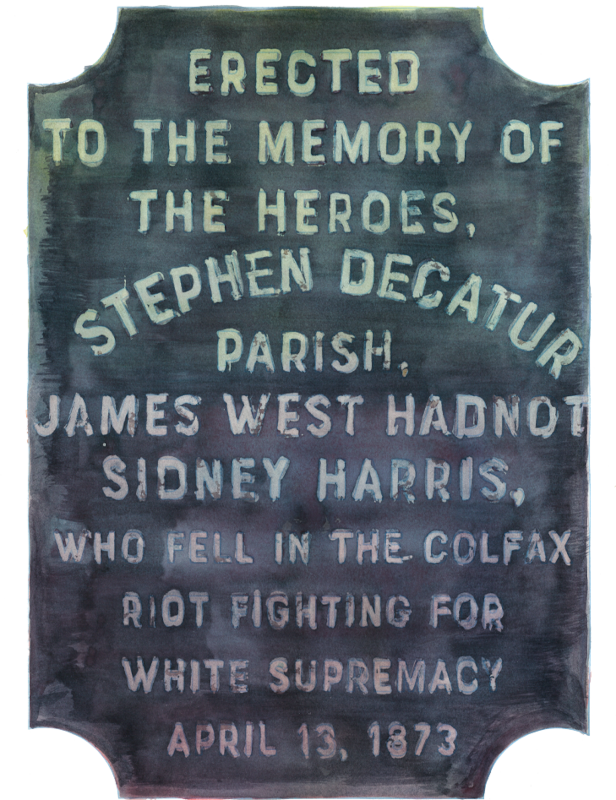

The Cruikshank decision made the lynching and violence of the Jim Crow era permissible and established legal precedent which permitted law enforcement to look the other way for decades in the face of overtly racist violence and terrorism (Pope, Harvard Law Review 2014). There is still no statue or memorial to the Black dead in Colfax. The Southern Poverty Law Center’s “HateWatch” blog notes that an obelisk commemorating the dead was erected in 1921 to honor the three white men who died in 1873. On the face of the obelisk is a plaque with their names, explaining that they died “Fighting for White Supremacy.”