Many call Louisiana’s River Parishes spanning 85 miles between Baton Rouge and New Orleans “Cancer/Death Alley.” This is because relative to the cancer risk in the rest of the contiguous United States, communities in this concentrated area adjacent to the oil and petrochemical plants experience unprecedented rates of cancer and other health ailments. Petrochemical, oil, and other industrial plants replace where once thriving black communities lived post-Civil war. Here, there is a clear connection between the environmental justice issues that arise in Cancer Alley and the close link with the history of slavery, Jim Crow Laws, and continued de facto segregation practices.

After the Civil War, the US Government passed a proclamation that redistributed land confiscated from white confederate landowners to former slaves, known as the “40 acres and a mule” as a form of reparations for the injustices of slavery (Darity and Darrity 2008, 656–57). However, the proclamation was met with substantial backlash. President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination resulted in the formation of Jim Crow laws, including “black codes.” Black codes remained enforced and in place until 1968 and were a way for Southern states to reinstate slave codes (John Wunder 2008) .

Black Codes impacted the formerly enslaved person’s mobility, such as restricting where they could live and work, the ability to acquire property, and put them under constant surveillance due to adjacent “vagrant laws.” As a way to be protected from Black Codes or being forced into sharecropping, newly-emancipated slaves in Louisiana established “freetowns” or “freedmen’s towns” where former slave quarters were located on previous sugar plantations (Brown and Moafi 2021) . Most of these freetowns, especially in Louisiana, were adjacent to defunct sugar plantations that are now mega petrochemical and oil and gas plants. This explains the proximity that black communities in Cancer Alley have to industrial plants in the present time. When looking at maps of Cancer Alley there are, at times, literal strips of a predominately black community next to industrial complexes (e.g., Denka Plastic Elastomers & Performance in Reserve, Louisiana). It is not by accident that these plants border former “freetowns.”

In response to the United Nations’ (“USA: Environmental Racism in ‘Cancer Alley’ Must End” 2021) March 2021 report, Louisiana Senator Bill Cassidy denied that Louisiana had an environmental racism problem stating, “I’m not going to accept that sort of slam upon our state” (Baurick 2021) . Cassidy’s response closely resembles an observation Charles Mills (Mills 1999) makes when he discusses the racial contract. In Mills’ discussion, he notes that the social contract is believed to occur between and apply only to white populations. So, when any deviations or injustices occur, they apply only to the white populations, and not to nonwhite populations. Thus, the institution disregards any further instances of injustices experienced by other races and ethnicities. Because Cassidy’s view of justice is institutional and not collaborative, he considers any injustices experienced by black communities in the River Parishes as being deviations or outliers and not of a sign of a racist institution.

Cassidy’s view of justice discounts social justice issues that lie outside of the institution. Amartya Sen calls such an account of justice institutional fundamentalism (Sen 2011, 83) . Cassidy is not the only lawmaker who views justice institutionally. However, the consequences of this accepted conception of justice leaves issues like environmental racism unexamined and neglected by lawmakers. Due to this neglect, environmental justice issues persist in the river parishes.

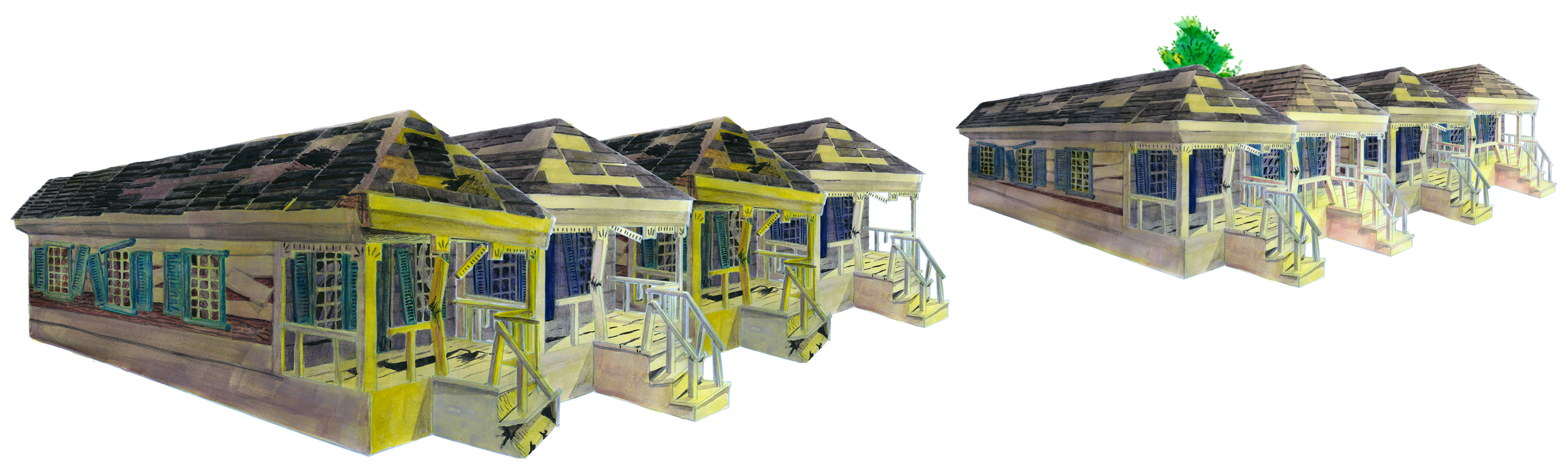

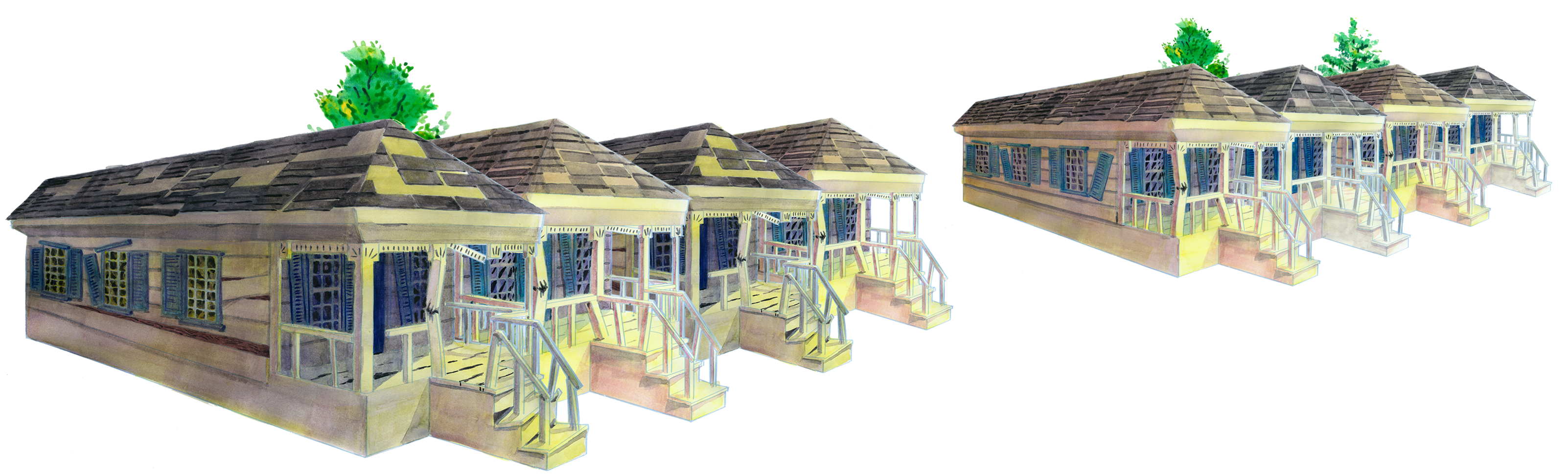

Communities suffer through a myriad of ways, like a depreciation of property value, outward migration, and diminished quality of life and well-being. Homes in the area show signs of consistent exposure to high concentrations to pollution, that present as deteriorating wood, metal, and unexplained discoloration on the outside of the homes. Due to new zoning laws, some industrial plants are less than 1,000 feet from homes, and some even share a fence line with homes—which is where we get the term “fence line communities.”

However, the hope is that through coalition-building and a continued push for accountability from lawmakers and corporations that incremental shift in policy occurs. So, instead of lawmakers normalizing racist policies and land ordinances, the hope is that they acknowledge the role and the legacy of racism. Once this acknowledgement occurs, then communities and lawmakers can collaboratively formulate future policy designs that promote equitable distribution of both environmental benefits and hazards.

While industry may not be completely eliminated from the area—although that is the ultimate environmental justice goal for local communities—there is a hope that in the very least future industrial development decreases. The expectation is that as industrial plants move out and more sustainable businesses move in, property values rise, younger generations either return or move to the area, and the communities once again attain a high quality of life and well-being. In a future without industry, communities can capture a photo of a thriving community and eco-system. One full of green, abundant, and flourishing magnolias, and beautiful and vibrant homes in the backdrop.

References

Baurick, Tristan. 2021. “‘It’s a Slam upon Our State’: Sen. Bill Cassidy Rebukes Joe Biden over ‘Cancer Alley’ Remarks | Environment | Nola.Com.” February 3, 2021.

https://www.nola.com/news/environment/article_98b5dd56-665c-11eb-993d-ab9537e3b12f.html

Brown, Imani Jacqueline, and Samaneh Moafi. 2021. “Environmental Racism In Death Alley, Louisiana ← Forensic Architecture.” 2021.

https://forensic-architecture.org/investigation/environmental-racism-in-death-alley-louisiana.

Darity, William, and William A. Darrity. 2008. “Forty Acres and a Mule in the 21st Century.” Social Science Quarterly 89 (3): 656–64.

John Wunder. 2008. “Black Codes.” In The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Volume 10:

Law and Politics, edited by James W Ely Jr. and Bradley G. Bond. Vol. 10. University of North Carolina Press.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/10.5149/9781469616742_ely.23.pdf?ab_segments=0%252FSYC-6168%252Ftest&refreqid=excelsior%3Ab6e31ce191f803d8eeca9ba39815f87a.

Mills, Charles W. 1999. The Racial Contract. 1st edition. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Sen, Amartya. 2011. The Idea of Justice. Reprint edition. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press: An Imprint of Harvard University Press.

“USA: Environmental Racism in ‘Cancer Alley’ Must End.” 2021. United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. March 2, 2021.

https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=26824&LangID=E.